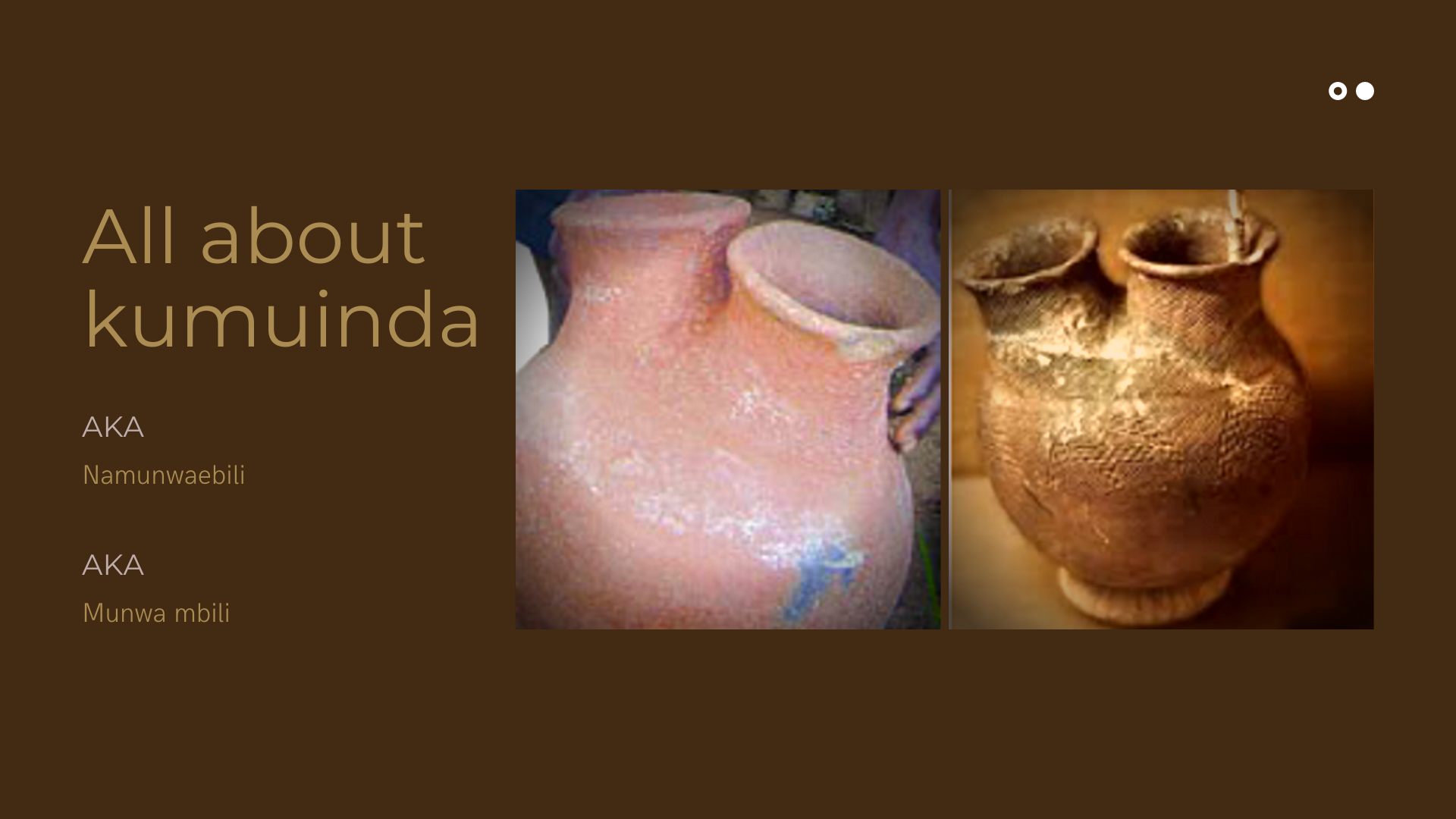

Have you ever come across a pot with two mouths? I usually see them at market places. One time while travelling in a matatu, I casually asked a passenger sited next to me the uses of a striking two mouth earthenware pot that he delicately held on his laps. Mr. Waswa, let’s call him that, was kind enough to school me. He started by giving me the Bukusu name for such a pot as kumuinda or namunwaebili.

All about the special kumunida pot that’s also known as namunwaebili

The elderly Mr. Waswa took me on a journey that not only made me know my history, but also reconnected me with my roots. It was a lazy Sunday afternoon; and with the matatu picking and dropping passengers at every stop between Kimilili and Sikata, we had plenty of time.

What is kumuinda, and what makes this pot also known as namunwaebili special?

Kumuinda or namunwaebili is an earthen pot with two necks and two mouths/orifices on a single body vessel. Namunwaebili in Bukusu language means “the one with two mouths”. The simple term ‘munwa mbili’ is also in common use nowadays. This pot is special because it is both revered and sacred. My people, Babukusu, commonly used this pot a call-response ensemble. Call it a “landline” whose connection terminated in the netherworld of omukuka and bikuka, our ancestors. Culturally among the Bukusu, kumuinda or namunwaebili featured during the birth of twins, rainmaking and in blacksmithing.

Bukusu traditions on kumuinda or namunwaebili.

Bukusu traditions on kumuinda or namunwaebili are about two things. The first touches on Bukusu pottery traditions. When it comes to making munwa mbili, our traditions are strict on who can make this special pot. The second thing narrows in on details groups of people who are advised not to use this post. This is because they are liable to suffer grievous harm if they made use of this ritual pot.

Bukusu traditions on making kumuinda or namunwaebili

Bukusu pottery traditions maintain that kumuinda or namunwaebili pot is made only by persons who can safely communicate with the world of ancestors i.e those unlikely to bring harm to themselves or the community. These special group of potters with a cultural pass to make namunwaebili are post menopausal women and old men.

Pre-menopausal women and young and middle-aged male potters risk being imbeciles if they make this ritual pot. Further, they risk having their skins turn pale and eventually losing not only their physical strength, but also their spiritual essence (heart, soul. mind, echiriri and breath).

Bukusu traditions on using kumuinda or namunwaebili

According to Bukusu traditions, kumuinda or namunwaebili was also not safe to use by this group. However, the potency of the curse wasn’t derived from the actual use of the pot but from the incantations before and during use.

Here’s a description of the uses of kumuinda

The following list of cultural uses of the two necked, two mouthed Bukusu traditional pot kumuinda or namunwaebili provide a feel of the context when using this ritual pot. Mr. Waswa flatly refused to elucidate details of certain musambwa such as blacksmithing where kumuinda is of central importance.

Instead he urged me to satisfy my thirst of knowledge on my roots, heritage and culture by speaking to primary sources on some of the uses of the pot. His exact words were: “I see you have a thirst for kimiima. If I am to tell you everything, it will make you lazy and complacent.”

He went on to add that the search for knowledge was one of those things in life that’s an anathema to the Bukusu proverb Sonywa munyngu chibili ta! His was to give me taste of the richness of our culture. He saw in me a thirst that could be quenched only if I drank from as many pots as I could. As a result, he was duty bound to add more wood to the embers of desire within me.

Therefore, what follows in a thematic rather than event based elucidation of the use of namunwaebili; as told to me by Mr. Waswa.

Namunwaebili use in brewing

Kumuinda was used to brew the first busaa during important traditional ceremonies. The likes of happy ceremonies such as traditional Bukusu circumcision and enganana. Or any other ceremony that celebrated the links between the living and their ancestors. The rest of the brew would then be brewed and drunk in the normal pot for such use known as embanga.

‘Other world’ things and kumuinda

Mr. Waswa explained to me that in his long life, he had witnessed a good number of witches being publicly shamed. All of them had been found in possession of with namunwaebili. In at least one of those instances, he recalls seeing witchcraft paraphernalia being stored in this pot. He explained that while he knew nothing about the musambwa of witchcraft, the likely explanation for this was coincidence. A chance happening that had to do with the age of those involved.

Bukusu culture has it that the likely people to be in possession of kumuinda are the elderly. He explained. As Mr. Waswa was to detail latter, the taboos associated with this ritual pot barred younger people from its habitual use. And given the power associated with kumuinda, the sighting of the pot during exorcism of witches may have only served to fortify the beliefs of the accusers.

Thanks to mob psychology, the collective at those public shaming suffered tunnel vision; and as a result became blind to the other explanations as to why an elderly man or woman could be in possession of kumuinda. That said, use of munwa mbili as a tool for communication with bakuka is its most infamous use.

A pot misunderstood

However, there were instances that were central to achieving harmony in the life of Mbukusu that needed the living to communicate with the ancestors.

As such namunwaebili was like any other tool. A panga, kumumbano or even fire. It was the reason why he could carry kumuinda in public, as he was, without fear of being mistaken. According to Mr. Waswa, this distinction was important. It is the misunderstood harping on ‘negative’ aspects of our culture that had made the modern African lose his way by turning his back on his way of life.

I couldn’t help but sympathize with Mr. Waswa’s point of view. As he went on to elucidate the other cultural uses of namunwaebili, my sympathy firmed into conviction.

Kumuinda use as a symbol to nudge abandonment of vice to embrace virtue

The perceived power of kumuinda was also used to warn someone who had been deserted by the spirit of mulembe; occasioning strife between themselves and their brethren. This person was to cease and desist from practicing the vice that was straining the fabric of society. By way of Mr. Waswa’s explanation, I picture munwa mbili as a lukhendu whose mere sighting is enough to kololosia embulu.

For example, if man A was suspecting a certain Wambumuli of having an affair with his wife, man A would invite the Wambumuli for a busaa drinking session. The host would then serve the busaa in namunwaebili. If it is true that the Wambumuli was having an affair his wife, it would be wise for the man fond of eating chimbeba to decline the drink. He was also to heed the warning and stop his illicit affair forthwith.

It is believed that if the Wambumuli shared the beer served in namunwaebili with the host distressed by Wambumuli’s thirst, the adulterer would surely die. How true is this? I don’t know. Hahaha!

Namunwaebili use in Bukusu traditional medicine

Munwa mbili was also used to treat eye conditions. Common folklore among the Bukusu goes that children with red eyes, those that science today attributes to allergies, should call for someone with kumuinda for help. When I asked my omuwekesia Mr. Waswa why this was the case, once again he urged me to go searching. So here I am still looking for a Bukusu traditional medicine man. Anyone with suggestions?