We explore the meaning of the Bukusu saying sikolonjo sialinda ekunda. In the process, we shed light on aspects of the traditional Bukusu land tenure system, pottery and circumcision.

Sikolonjo sialinda ekunda in English

“Potsherds look after (take care of) the land.”

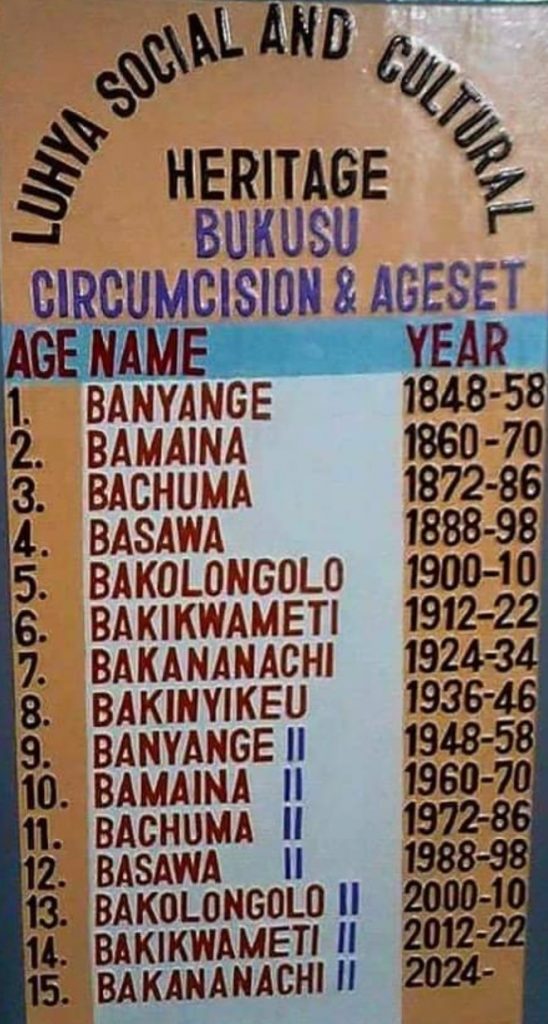

It was during sisingilo of Bachuma II, between 1972 to 1986, when the welfare of the boy child took a new prominence among the Bukusu. As any keen observer of world history will note, this period coincided with the latter ebbs of second wave of feminism. Global protests with the rallying call “The personal is political” calling for equality and non-discrimination were loud; In a teenage Kenya, this message was being amplified by the television sets and radios of the new Kenyan elite.

(Wo)men of Iron?

Already, the Kenyan people had been sensitized to the changing times by the 1969 election of the first elected woman MP Grace Onyango to represent Kisumu Town Constituency. Not far from Kisumu, the thud generated by the annihilation of Arthur Ochawanda at the polls by the diminutive Prof. Julia Ojiambo, Nadongo Ofwokha, must have been deafeningly loud.

Not so long after the exploits of Grace Onyango, Prof Julia Ojiambo became the the first woman to defeat a man in a political contest in Western Kenya. In the 1974 election, she was elected to represent Busia Central Constituency; her triumph was symbolic. As a result of such radical change in our politics, the way we govern society, the strings of the fabric our, by then, largely tribal ways of life were painfully taut.

That said, the cultural significance of sikolonjo among the Bukusu much predates this period. Thus it can be argued with some accuracy that indeed there wasn’t much that was special about the age set of Bachuma II – except by the divine hand of our ancestors.

Vindu vichenjanga

Actually, in view of the new world brought about by the second feminist movement, the coming to be of the sisingilo of Bachuma following traditional Bukusu circumcision can be said to be reactionary to the spirit of the times. The message at this time called on women to examine how their personal lives were being adversely affected by sexist power structures, and take action. This was happening in a Kenya that was still deeply patriarchal.

This tension between new and old ways was evident in western Kenya: On one hand we gave Kenya and the world Prof. Julia Ojiambo & Co, on the other hand we celebrated an age set named Bachuma. In Bukusu language Bachuma means: ‘those of iron’.

Surely there are other reasons why such a name for an age set, but as we will see further down this article, the name Bachuma might as well have been a reaction to the power shift that was taking place. It is my thesis that insufficient interrogation of the worldview presented by he second feminist movement might have been prejudicial to otherwise sound aspects of Bukusu and Luhya culture at large.

In particular, stipulations of our culture whereby land culturally represents belonging; and therefore by owning land, the vulnerability of being considered ‘other’ and therefore not worthy is removed. These cultural events that dominated the 70s inexplicably put to shreds part of the body of traditional Bukusu land tenure system.

Conquest by Way of Sikolonjo: Of Belonging and Land in Bukusu Culture

Among the Bukusu (as a matter of fact the Luhya), land inheritance was patrilineal. Generally, it was your father who’d give you land where you’d build your home. This land, you’d then pass onto your sons. As so, generally, ancestral land went to the boys.

Allow me to emphasize one more time – generally. Meaning, the womenfolk too had their right to land and land rights; and there are a clutch of instances where land inheritance is not patrilineal. Beyond these instances, it is through sikolonjo, the potsherd, that women’s right to land was exerised.

Sikolonjo and land ownership

The cultural significance of sikolonjo stems in large part from the customs, traditions and symbolism of the craft of pottery. Sikolonjo are unlike the pot they come from. While the pot is fragile, potsherds are incredibly tough. Often, sikolonjo outlive the generation that made the pots that nee them.

In Bukusu culture this longevity, like the male line of progeny, is symbolic of continuity and permanency. Simply put, the presence of sikolonjo in a farm is indicative that there were people before who called that land home. While this meaning of sikolonjo comes from patriarchy (the firing of pots is symbolically equated to the fire ‘imbalu’ that an initiate, omusinde, undergoes during circumcision), as pots are considered a ‘woman thing’, the matriarchal significance of sikolonjo cannot be ignored.

Flag post

It is the women who use the pots and leave behind potshards. This means therefore, that it is the women who put a mark on the land. It is them who plant a flag on the land conquered by their husbands (via their bloodline) and proclaim the territory as belonging to her and husband’s progeny.

By extension, therefore, my view is that in Bukusu culture the value of a man as a conqueror of territory is naught if there are no women. The woman is needed to take care of the land. Her presence, occupation of the conquered territory evidenced by the use and need of household ware such as the pot, the ancestor to sikolonjo, is what seals ownership of that land. Thus once boundaries of the territory are defined by likongwe, it is the divine honor and right of the woman to take care of the land by tending it: sikolonjo sialinda ekunda.

In this way, sikolonjo is the way a man is made by the woman. There cannot be man with full rights to inherit sons if there’s no woman. More trivially, why would one need pots if there was no one to fetch water for? Cook for? Brew for? It is by way of the woman’s sikolonjo that the masculine ensemble to bless their progeny and fulfill the male urge to confirm “I was here”.

Like a father

Therefore, in postcolonial times and as land tenure became westernized allowing for land to be sold to others i.e. those who can’t inherit it as they are not part of the bloodline, the presence of sikolonjo in a farm served as identity markers of place/home/ belonging.

This means that even if one bought full rights to land in a willing buyer-willing seller arrangement, one had to always remember that the land represented a people and their history that has to be respected. In fact, a common refrain among the Bukusu is: One who sells you land gives you a home and is therefore like a father.

Bukusu sayings and Proverbs related to sikolonjo sialinda ekunda

The following Bukusu sayings and proverbs stem from the saying sikolonjo sialinda ekunda. They offer more context on issues like the traditional Bukusu land tenure system.

Omwana we sisecha sikolonjo silinda mukunda; owe sikhana kukhele matuma ngila

Translated as: boys are potsherds that take care of family land while girls are frogs that cross roads; as in, they get married.

Omwana omusoleli or we sisecha silinda mukunda; owe sikhana kukhele matuma ngila lakini omukoko silundu.

Translated as the boy child is like potsherds that take care of the land, a girl is like a frog that crosses the road, but she is the kitchen garden.

Subscribe to Mulembe Weekly

Get culture, language, stories and discussions in your inbox every Friday 5 PM East Africa Time