Given its esteem as a corner of the world replete with cultural treasures little wonder then that, justifiably curious, we watched on when the logooli nation of mulembe nation mourned its fallen son mkevi Ngori. Ngori was a respected traditional circumciser who was the last kind.

I had expected a much larger crowd. But, amwavo this is not to say the villagers – man and woman, child, youth and not so youth drawn from as far as Gambogi, Chavakali and Shamakhokho – made an embarrassing gathering. Far from it actually. But as I hurriedly circled the mass of my people, bedecked mostly in virgin white, nipping towards a far corner of Mbihi primary school field where I guesstimated that I would easily blend in, it was a comparatively much more breezy spot from where to catch the events of the day. It was nothing like any chaotic market day in Luanda or Cheptulu; but there were people: thousands. Could be the expanse of the school field made it appear like they were far less a multitude than they actually were.

In that corner of refuge, the camaraderie among the steadily growing lot of us -curious onlookers massing up on the fringes of the four acre or so school grounds in Wamuluma/Lugaga Ward, Vihiga County- provided the perfect backdrop for an anticipated feast on the ways of our forefathers.

For such a solemn occasion, one not cultured in our ways would have found the air too electric. As the crowd was more intimate, the air wasn’t in keeping with the humongous as the sea of humanity on site. In some ways, it reminded me of Wambari (Mbale Town, Vihiga) every 26th of December when we gather to celebrate uvutamaduni at the annual Maragoli Cultural Festival. In defiance of the solemnity of the occasion it was just as dense gathering, and full of color too.

Rain or shine, we had come out in our thousands because such days and such honor is reserved for guys like Ngori.

A Day In September

That said, that day in September of 2017 served to remind us that uvutamaduni would be different that year. As in, sad different. What a trying year 2017 was proving to be. 2017 was the year where we saw chikhungu (army worms) invade our farms and plunder our maize harvest. Kumbe, that was just the beginning. 2017 was also the year after the latest once-eight-yearly Maragoli circumcision season.

That season, that turned out to be the last work of Ngori the circumciser, had given us the age-set “Ugatuzi” aka “Devolution”. We people of Mulembe had celebrated the advent of devolution, but as the first full cycle of this governance system came to an end, it was true that it was Not Yet Uhuru.

The toll of politics on Kenya that 2017 was plain even to the casual observer. But in the midst of battles between those seeking to be called omwami, life trudged on. For the Mulogoli of the North, what this meant was the worst had befallen the last of their ‘true’ traditional circumcisers: A custodian pillar of Mulogoli ways. As it goes then 2017 was also to be the year when Ngori was not be there to be celebrated with other omwamis at Uvutamaduni; as Ngori, The mkevi, was no more.

And The Rain Fell And Fell, Meaning Ngori Was Happy With His Send Off

This chosen day of celebration of the life and times of a Maragoli cultural icon had started off as a cargo shorts, tee shirt and Akala kind of day. But without much warning (more appropriately so enthralled I was with the action at the center of the primary school ground to notice the shifting weather) the skies turned grey.

And it rained. A good half on hour or so of rain. A downpour heavy enough to fill (up with storm water) the ceramic tile paved six by six foot hole in the earth awaiting the remains of Maragoli’s last ‘true’ traditional circumciser, at his home just off the Mbihi- Kidundu dirt road. In Logoli culture, rain is the perfect send off. With the flash showers, the heavens had, had their say. Now all was left was for us the living to do our bit.

And so, with the chaotic order that only African rain can bring, we packed ourselves under the cover of iron sheets that shade over the concrete paved verandas outside the CDF built classrooms and waited. Drenched in the inevitable concoction of pungency of adult human odors, we faced towards the center of the school grounds where the day’s program trudged on unperturbed.

A few murmurs here, there, but silence mostly. The time for talking was over. Now was time for eyeballs. The cold air was heavy with expectation only that we don’t know what to expect. Were it the burial of any other village folk, It would have been easy to guess what kind of action to expect. But not today. Not for the very last of a kind: mkevi Ngori, The Traditional Circumciser.

AS YOU LIVED AND SO WILL BE BURIED

This guessing game, of anticipated matanga action, is possible because we the descendants of Mulogoli hold the belief that a person’s burial serves as a last ode to their person. Meaning that for a person with a turbulent personality, at the very least, a sprinkling of drama is expected here and there on the day of their burial.

Based on this common knowledge, the village drunk’s funeral is expected to be patronized by his or her brew-mates in full swagger. Take the case of a funeral that took place not so long ago and not too far from here. It was the burial of a major jamabazi from the city. A son of the soil rumored to be a chief gangster and said to have been murdered by the police in a deal gone awry. Your guess is as good as mine as to the collage of the attendees of that funeral. Even my senge, who’s at that age where you don’t skip funerals in the hope that the favor will be returned soon, kept away. So did my cousins who are disco matanga adherents. They did this in keeping with the decision of the entire village not to honor such shame among them with their presence, and so I hear.

Two cultures and a funeral

In spite of their boycott, the burial of our Larry Hoover was filled to the brim. Filled with colleagues – from gang mates, ride and die vixens, to cops, politicians and village wannabes -the unauthorized takers of chicken, sugarcane and the likes. But for a man, a complex tapestry of a man, like Mkevi Ngori, there was no telling of what the funeral would be like:

Would it sway to embrace the exuberance of Ngori’s Idakho ancestry? Or will the equanimity of his Maragoli naturalization emerge? Maybe the funeral will be church-y affair given his rank among PAG faithful. Could be that the Musambwa of being the custodian of The knife as traditional circumciser would reign supreme. How would these two worlds, and two cultures sit together in such an emotionally volatile moment? After all, this a sweetener possibly- there laid man who had practiced polygamy (to great success I might add)- in Maragoli land!

NGORI: Traditional Circumciser With Gifted Hands

And so we stood, breaths baited, our feet wet from the steady patter of raindrops dripping on to the raw earth just yonder our step. Hitting up the soil coloring our feet blood red just like the swift action of Ngori’s knife would in his heydays. Our ears lent to speaker after the other singing praises of mkevi Ngori The traditional circumciser.

” Ngori alichonga kalamu za vijana vizuri zikaweza kauandika vizuri.”

Says a peer, a practitioner of traditional circumcision all the way from Tiriki. We Maragolis cheer and clap at this. A great service to us that this adopted son of Mulogoli, who we had gathered to honor, had offered. As the custodian of the right of passage – traditional circumcision – that ushers in the next generation, we remain thankful as a community. By our cheers and pearls of naughty laughter, we all seem to agree that Ngori had an unblemished record as a surgeon: no ‘decapitations’ or other penile injuries.

“Mikono ya Ngori ilikuwa safi. Alifanya kazi yake vizuri bila shida. “

Offers another traditional circumciser amid cheers. This one must have been from Mkevi Ngori’s maternal roots in Idakho. Needless to say, the people from Idakho were there well represented half mourning and half proud. Proud at how Ngori took good care of their musambwa.

Ngori’s clean hands: Celebrating an unchequered career of an astute traditional circumciser

As a “foreigner” if Ngori’s hands had been bloody, he might as well have said goodbye to his dreams of being a traditional circumciser. And I am being polite here. You can imagine Ngori’s fate had his first initiate been a hemophiliac! Lets not go there. Anyway, Maragoli oral literature talks of “the hands of the circumciser” as being the primary cause of adverse bleeding events during traditional circumcision. Such that a traditional circumciser with “bloody hands” has a predilection for his initiates to bleed furiously.

Modern science of course talks of hereditary disease conditions such as hemophilia being responsible for such tragedies. At the very least, my street acquired medical anthropology tells me something about us Maragolis. Ngori’s unchequered career as a traditional circumciser that spanned over half a century reveled to s one thing: the low prevalence of inherited/ acquired bleeding disorders among the Maragoli.

CONTROVERSY

While at the refuge corner the air was less spirited as is was the case at the heart of the carnival at center of the field, it shouldn’t be mistaken that we were less entertained. Yes we stood deep in North Maragoli, among those who pride themselves to be calmest of the Mulembe brotherhood; but even I, a born town, would not have been fooled into expecting a quiet solemn affair.

The death of traditional circumciser Ngori, a man of two worlds and two cultures, had generated sufficient village chatter in the week preceding his burial ceremony. Talk in mukidaho, mumaganisa and mukidari had postulated on the expected clash between the worlds and cultures he straddled. Thus, in search for this drama, we traveled North West, braved the rain, soaked leather shoes and socks all in the quest of satiating our curiosity.

Having received the knife from his maternal uncles, Ngori had transcended barriers: clan-ism, sub clan- ism and sub tribe tensions. He had crossed rivers and valleys in his adopted land, burdened by the sacred task of drawing blood and soaking the earth with it in order to make men of boys. As he approached his sunset years, Mkevi Ngori had done what was expected of him culturally as a traditional circumciser. Just as he had received The Knife from his maternal uncles, he was duty bound to pass on the knife to the next generation.

Who Inherits The Knife?

But just as it must have been at the beginning of his career, questions abound.How can a son of Idakho circumcise the sons of Mulogoli? was the question at the beginning; and now at the end of his stellar career, the question was: Does Ngori return the knife to Idakho where it came from? Or does The Knife remain in Maragoli now that it carried the spirits of Mulogoli? If it remains, who then to give the knife to?

It is at that last point where the inter-clan, sub-clan and sub-tribe wars that Ngori had expertly navigated throughout his life threatened to rear its head. In the moons preceding his ailment and now death, rumors were rife of an undeserving family conniving its way to assume custody of The knife. But as Ngori had lived and so he died and was buried – controversy but no drama. By the time we gathered by the playground, Ngori lying in state, all differences had been ironed out and balance achieved.

Celebration of a Life Well Lived

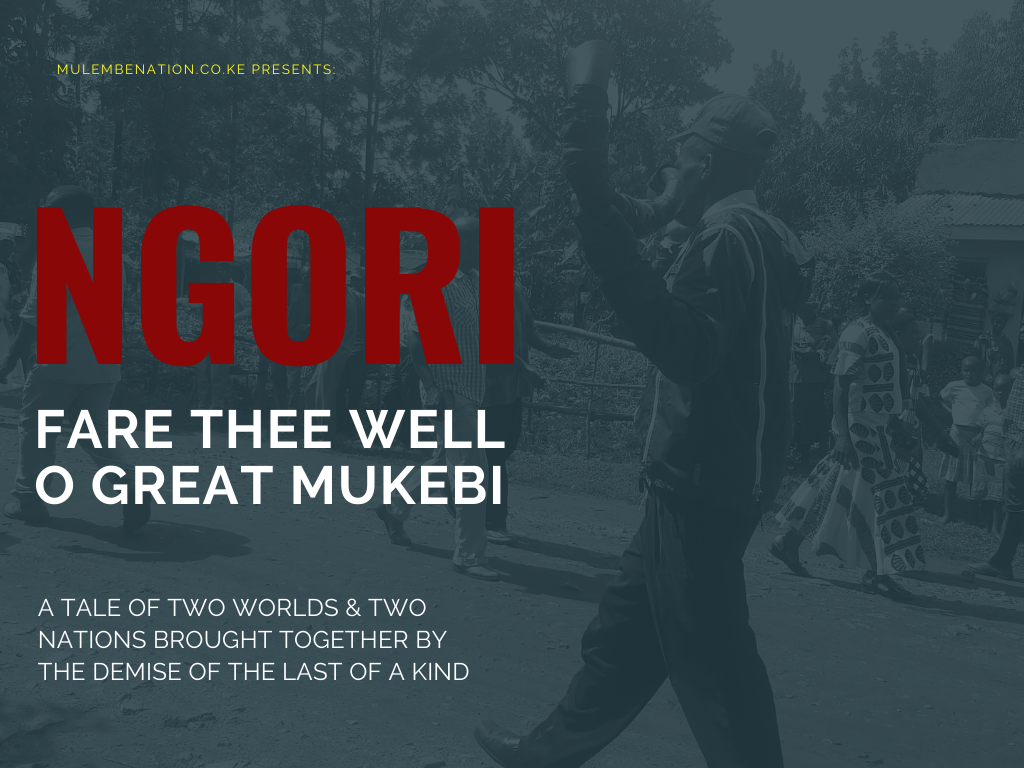

If a single picture could tell the tale of the ways of the contemporary mulembe nation, this has to be it. In this picture, we see a traditional circumciser, clad in full traditional circumcision regalia, performing a burial rite with Afro-Christian roots.

Oh! Yes, this was a fitting an ode to a life lived as the perfect tapestry of cultures and worlds. That Saturday 9th September of 2017, mid-morning to mid-afternoon at Mbihi Primary School grounds in the midst of rain, we all gathered. His initiates and those cut by other knifes. His Idakho and Maragoli relations. Ngori’s christian and traditionalists contemporaries. We all gathered to celebrate Mzee Ngori. Ngori the PAG church elder and Ngori The traditional circumciser. The community elder, father, grandfather and friend.

As we did, drums, clapping, song and dance of Afro-Christian celebrations of his faith were perfectly punctuated by the steady din of the unmistakable call of mkevi. All in perfect harmony. But where was that well-known call of mkebi coming from?

Christianity and Traditionalism Coexist: A Testimony To A Man Who Bridged Cultures

While it was easy to pick mkevi Ngori’s peers from those he fellowship with in church, mourning family and curious onlookers by way of their dress as the circumcisers donned leopard skin dress, Columbus monkey head gear and were constantly fiddling with their circumcision knives, one traditional circumciser stood out from the bunch.

His version of morning was responsible for that steady din of the unmistakable call of mkevi. His work percussing a metallic instrument rode over the well known, PAG energized, Maragoli Christian dirges. He was a bronze skinned, gently muscled lad decked in full traditional circumcision gear. A young man possessed with the spirits of those entrusted with the power of making men out of boys.

By way of his constant circling of the gathering in clockwise fashion; steady pace, game face on, stoically stubborn in his tribute to mkevi Ngori he pulled us into his misery. More importantly, he reminded us that Ngori’s spirit lived on. Not once did his full-blooded mourning distract the church service. Watching him do his thing, I couldn’t help but smile to myself. Oh, yes! There will be another Ngori.

Where Were The Women?

No women were allowed to witness the final burial rites. Similarly, uncircumcised males or those circumcised at hospitals were also forbid. Like in the burial of any other full Maragoli adult male, only bulls were slaughtered. In similar vein, given his advanced age, he wasn’t not to be lowered to ground while the sun was still high.

Moreover as a special ode to his service to the community, new initiates were made over the mourning period. Some more were made into men just before lowering of Ngori into his final resting place. These initiates will know their ageset name later. Moreover, they will belong to the age-set that will come into place in next cycle of the Maragoli traditional circumcision season. The season comes every eighth month of the eighth year.

All other rituals not mentioned here, remain with those privileged to witness and perform them.

May you Ngori The Circumciser rest in peace. Pass on our regards to Joseph Daniel Otiende, Moses Mudamba Mudavadi, our fathers and mothers gone before.

Subscribe to Mulembe Weekly

Get culture, language, stories and discussions in your inbox every Friday 5 PM East Africa Time

This is a great piece. I really appreciated and enjoyed the edutainment. Thank you.

Appreciate your kind words. Thanks for reading.